-

process information to discuss Einstein’s and Planck’s differing views about whether science research is removed from social and political forces

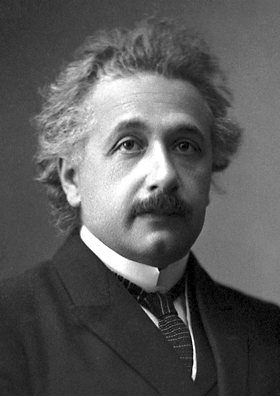

Science is a powerful instrument. How it is used, whether it is a blessing or a curse to mankind, depends on mankind and not on the instrument. A knife is useful, but it can also kill.

Einstein

This 'dot point' from the NSW Physics Syllabus is at best woolly and ambiguous and at worst misleading because it seems to imply that a great gulf existed between Einstein and Planck when in fact they were lifelong friends and seemed to have much in common and a great respect for each other.

This 'dot point' from the NSW Physics Syllabus is at best woolly and ambiguous and at worst misleading because it seems to imply that a great gulf existed between Einstein and Planck when in fact they were lifelong friends and seemed to have much in common and a great respect for each other.This friendship grew, as one might expect, firstly from their science. Einstein had realised the real significance of Planck's quantum hypothesis when he incorporated it into his work on the photoelectric effect. Planck was initially sceptical, but when Einstein finally convinced him, Planck offered Einstein a professorial appointment at Berlin University where Planck was the Dean. The two became close friends and met frequently to play music together. They had much in common, they were both physicists, they were both leaders in the development of quantum theory, and they were both German (though by this time Einstein had taken out Swiss citizenship).

They had their differences. Planck was a proud Prussian (though not an extreme nationalist) while Einstein was a Jew who gave no allegiance to any state and believed that the world would be better off under a single world government.

These differences came to the fore at the start of World War I. In 1914 Planck signed the infamous "Manifesto to the Civilised World", a government sponsored proclamation endorsed by 93 prominent German scientists, scholars and artists, declaring their unequivocal support of German military actions in the early period of World War I.

They had their differences. Planck was a proud Prussian (though not an extreme nationalist) while Einstein was a Jew who gave no allegiance to any state and believed that the world would be better off under a single world government.

These differences came to the fore at the start of World War I. In 1914 Planck signed the infamous "Manifesto to the Civilised World", a government sponsored proclamation endorsed by 93 prominent German scientists, scholars and artists, declaring their unequivocal support of German military actions in the early period of World War I.Einstein, in contrast, retained a strictly pacifistic attitude and responded by signing a 'Manifesto to Europeans', which challenged militarism and 'this barbarous war' and called for peaceful European unity. This act by Einstein almost led to his imprisonment, being spared by his Swiss citizenship. These differences were short lived. In 1915, after several meetings with Dutch physicist Lorentz, Planck revoked parts of the Manifesto. Then in 1916 he signed a declaration against German annexations.

Between the wars Planck's views on the independence of science firmed. He argued that science should be an independent pursuit of knowledge, not controlled by the needs of the state or industry. In this, Planck was at one with Einstein. As the Nazis increased their power in the 1930s Planck adopted the strategy of 'persevere and continue working'. The strategy became more difficult due to the Nazi treatment of Jews which Planck openly and bravely protested. He even had the courage to discuss this matter directly with Hitler. He tried to keep science independent of politics and resisted moves by the Nazis to focus scientific research towards the needs of the military and the state. In 1937, he resigned as the President of the pre-emminent Kaisser Wilhem Institute after it was reorganised by the Nazis to serve their purposes.1

During this time Einstein, who was Jewish, had left Germany. He opposed the German militarism but ironically, the actions of the Germans caused him to temporarily abandon his pacifist stance. “Organised power can only be opposed by organised power. Much as I regret this, there is no other way.” In 1939 Einstein was persuaded to lend his prestige by writing a letter, with Leo Szilard, to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in order to alert him to the possibility that Nazi Germany might be developing an atomic bomb and urged the Americans to do likewise. Roosevelt's response was the Manhattan Project which created the first nuclear bombs, used not against the Germans who had already lost the War in Europe, but against the Japanese as one of the final acts of the War in the Pacific. In his later years Einstein regretted signing these letters “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I would not have lifted a finger”.

So at the beginning of WWI, Einstein was the pacifist while Planck was urging the scientific community to support the war effort. In contrast, at the beginning of WWII, Planck was resisting the militarisation of scientific research while Einstein argued for scientists to aid the military in development of nuclear weapons2. Both had justification for their actions at the time, but both came to regret advocating the support of science for military purposes. Both became advocates of the pursuit of science for the common good. In summary, their relationsip was marked much more by what united them than bywhat divided them.

References

Pais, Abraham (1982) Subtle is the Lord: The science and life of Albert Einstein.

http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1918/planck-bio.html downloaded 27 Apr 2001

http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1921/einstein-bio.html downloaded 27 Apr 2001

http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/history/Biographies/Planck.html downloaded 27 Apr 2001

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Planck downloaded 27 Apr 2001

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albert_Einstein downloaded 27 Apr 2001

Notes

1The institute would later be renamed the Max Planck Institute in his honour.

2Planck's son, confidant and friend, Erwin Planck was executed by the Gestapo for alleged involvement in the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler in 1944.

No comments:

Post a Comment